| Contact |

| Back | Next | Home |

Conduction,

Insulation and Electric Current - 1729

Stephen Gray (1666-1736)

The Discovery of Electrical Conduction and Insulation

(UNDER CONSTRUCTION)

Stephen Gray was born in Canterbury, Kent, England December 26th 1666. His family were carpenters and dyers. In his writing, Gray has the confidence of a self-taught man. He was close friends with Newton's rival John Flamsteed (of Denby, Derbyshire - the first Astronomer Royal) which some believe led to Newton (then president of the Royal Society) blocking the publishing of several of Gray's papers on electricity17.

His electrical interests first appear in a letter of 1708 to Hans Sloane, in which he described the use of down feathers to detect electricity. He is obviously fascinated by lights produced by rubbing a glass tube to charge it and realizes electricity and the lights are related. The idea of an effluvium released from the tube is giving way in his thoughts to ideas of a virtue, something akin to gravitational attraction and electrical conduction.

While a Pensioner of the

Charterhouse he carried out, in his sixties, his experiments on electricity.

|

|

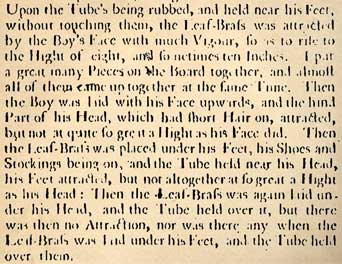

These are excerpts from letters sent from Stephen Gray to Cromwell Mortimer, documenting Gray's landmark discovery of electrical conduction and insulation. They are from "Two letters from Gray to Mortimer, containing a farther account of his experiments concerning electricity", printed in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society # 37, 1731 - 32.

I am presenting the

step-by-step details of Gray's experiments because I think they make a good

illustration of the method of inquiry of the time.

| Note: Printing type of the period used a character similar to a lower case "f" in place of the lower case letter "s". For example the last line at left reads: "fo as to give them the fame property..." You get the hang of it after a little practice. |

Gray's Apparatus

For his experiments, Gray used a simple

3.5 foot glass tube, 1.2" in diameter. When rubbed with a dry hand or dry

paper the glass would obtain an electric charge. These glass tubes were

popular - they were much more portable and less expensive and than the large

"electrical machines" of the time. It was with such a tube that

Benjamin Franklin was introduced to electricity1.

|

|

The Experiments

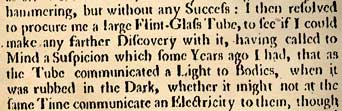

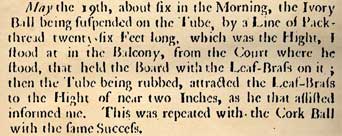

Gray begins with some background on his reason for conducting these

experiments (Fig. 2); he tells how he became interested in whether electric

effluvia (scientists of the time believed electricity was a fluid) could be

communicated between charged objects (bodies). This question came up

as a result of his observation that his "tube communicated light to bodies",

i.e. he saw sparks jump from the tube to objects held near it.

|

|

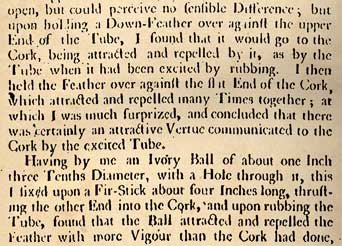

He describes how he keeps both ends of the tube corked so as "to keep the dust out when not in use." He notices that the charged tube not only attracts a feather to the glass, but to the cork as well (Fig. 3). From this he concludes that the "attractive virtue" is passed to the cork from the tube. Being a diligent observer, Gray proceeds to examine exactly how far the virtue can be passed. He attaches an ivory ball to a four inch piece of wood and inserts the other end of the wood into the cork. He finds that not only is the attraction and repulsion passed to the ball, it is even stronger than on the cork.

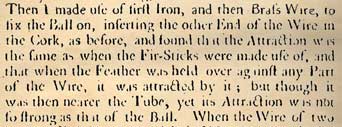

The first use of metal wire

Gray proceeds to try

other materials between the tube and the ivory ball. He tries iron and

brass wire (Fig. 4) which does pass the virtue, but vibration of the wire

caused by rubbing the tube interferes with the experiment. So Gray

uses pack-thread in place of the wire, and inserts a loop to absorb the

vibrations of the tube. Again, he finds the effluvia is passed to the

ball.

|

|

|

|

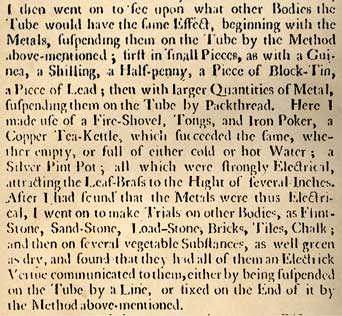

In Figure 5 we find Stephen Gray searching

around his house for any object that might be suitable for a test. He

focused on metals first, testing several coins, pieces of tin and lead, a

fire-shovel, tongs and iron poker, a tea-kettle (both empty and full, hot

and cold water!) and a silver pint-pot. He found all of them to be

conductive. Next he searched out what non-metal objects he could find,

including several types of stone and some green vegetables, all of which he

systematically hung from his harness of pack-thread, and all of which passed

the "attractive virtue."

|

|

Over the next several days, Gray continued to experiment by extending the length of his apparatus. I should point out here that these experiments were performed vertically; that is, the assembly of rods, pack-thread, wire, etc., was hung vertically with the ivory ball at the bottom and the glass tube at the top.. I believe Gray did this out of simple practicality (hanging the thread required no supports to hold it above the floor, unlike a horizontal run would require), not because he believed the effluvia needed to run downhill. In any case, he extended his apparatus higher and higher, from 26 feet (fig. 6) until he was as high as he could go on his balcony and still the virtues were carried the full 52 feet.

|

|

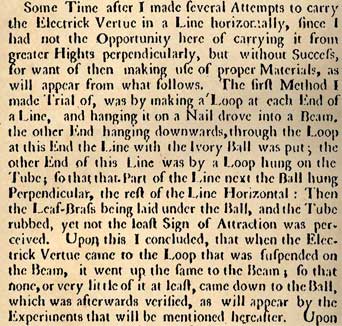

A horizontal run

Since he had reached the upper limits of the house The next logical step was

to run the thread horizontally. His account of this is shown in Fig.

7. He attached one end of the thread to a nail in a beam and the other

end looped over the tube. This time when he rubbed the tube nothing

happened. He correctly concludes that the fault is in the connection from

the thread through the nail to the beam; i.e. the 'electrical vertue" is

passing into the beam rather than being carried to the ivory ball.

At this point he decided to give up on the horizontal approach and perform more experiments with a vertical conductor. But where was he to find a building tall enough? The answer, of course, was London. And the building? Even as he was packing up his apparatus, Gray was planning his next experiment: A vertical drop from the top of the cupola of St. Paul's Cathedral.

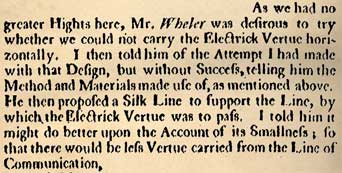

Before heading to London, Gray visited Otterden-Place and his young friend Granville Wheler, who lived in a large house that would be very suitable for further tests. After several successful attempts, and reaching the highest point of the house, Wheler suggested they try a horizontal span (see fig. 8).

|

|

Gray explained that his previous attempt had failed, and his theory as to why. Without understanding it's properties as an insulator, Wheler then suggested the try to suspend the line using silk thread. Gray agreed this was worth a try, thinking that less of the electric vertue would leak out through the small silk thread.

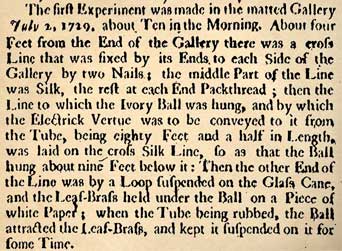

On July 2, 1729, they assembled the experiment shown in Fig. 9, using silk thread and poles to hold the packing thread above the ground. He describes the set up in figure 10.

|

|

|

|

With a run of 80.5 feet, the leaf-brass was attracted to the ivory ball.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Contact |

| Back | Next | Home |